Huawei has hit upon a new strategy for fighting back against the US: leveraging its massive suite of technology patents to try and force American competitors to fork over billions of dollars. And its first target is Verizon, one of its biggest American competitors in the race to become a global leader in 5G.

As Reuters reports, Huawei has told Verizon that it should pay licensing fees amounting to more than $1 billion for the more than 230 patents held by the Chinese telecoms giant.

The plan has been percolating since before the White House blacklisted Huawei: Verizon should pay to “solve the patent licensing issue,” a Huawei intellectual property licensing executive reportedly wrote in February.

The patents cover networking equipment for more than 20 of Verizon’s vendors, and those vendors would, in theory, indemnify Verizon. Some of these firms have been approached directly by Verizon. They range from core networking equipment and wireline infrastructure to IoT technology, according to sources cited by WSJ.

For nearly a year now, Washington has been lobbying its allies to block Huawei equipment from being used in their 5G networks. That feud intensified in December, when Canadian authorities arrested Huawei’s CFO, Meng Wanzhou, at the behest of the DoJ. The DoJ is now seeking to extradite the Huawei executive over allegations she lied to banks about Huawei’s relationship with certain affiliates in order to help the company circumvent American sanctions on Iran. Washington’s biggest complaint to its allies is that Huawei is bound by Chinese law to help state intelligence spy on foreign governments and civilians, if asked. Beijing and Huawei have denied this, but evidence of ‘back doors’ in Huawei equipment has been uncovered in the US and in Europe.

Verizon and the other companies have reportedly notified the US government about Huawei’s demands, which they suspect are motivated by the ongoing feud between Huawei and Washington.

A spokesman for Verizon declined to comment to Reuters, claiming it’s a sensitive legal matter. Though he did say that the issue is “bigger than just Verizon.”

“These issues are larger than just Verizon. Given the broader geopolitical context, any issue involving Huawei has implications for our entire industry and also raise national and international concerns.”

Of course, given Chinese companies’ well-documented history of stealing American technology either via forced technology transfers in exchange for access to the Chinese market, or straight-up corporate espionage, the irony in Huawei’s demands is more than a little ironic.

Huawei “Spent All Their Resources Stealing”, Stunning New Exposé Shows

The accusations of Huawei stealing trade secrets from across the world are hitting a fever pitch, thanks to a new Wall Street Journal expose that blows open accusations of theft and stealing of trade secrets.The article includes insights from lawsuits, Huawei’s competitors and former employees. Allegations run the gamut against the company: from its business practices, to the science behind its 5G, all the way down to copying the text it used in its user manuals.

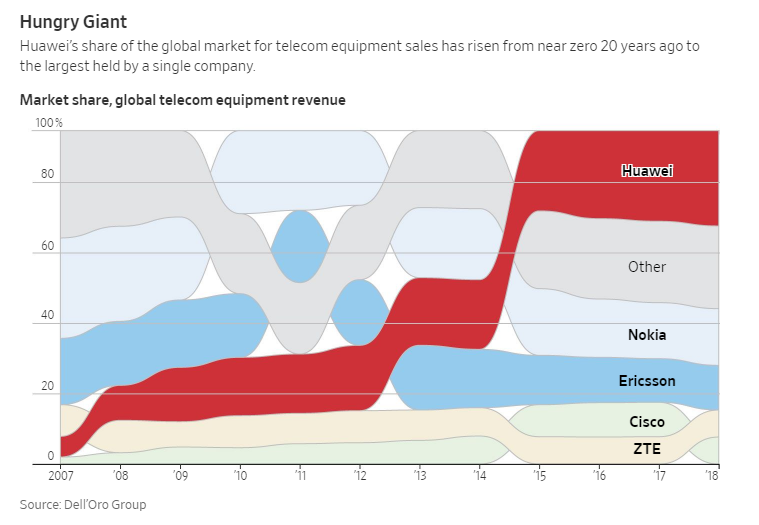

Huawei has grown into China’s global technology powerhouse, as a leader in 5G networks and giant maker of telecom equipment. The company employs 188,000 people in more than 170 countries and sells more smartphones than Apple. It also provides cloud services, manufactures microchips and runs internet cables undersea that help route global traffic.

The United States is finally following in the footsteps of places like Australia and putting pressure on the company out of concern for national security. Just last week, the Trump administration unveiled measures to help cut Huawei off from American suppliers and stop it from doing business in the United States. The administration believes that the company takes its orders directly from Beijing and that its standing as the top telecom company in the world makes it a powerful tool for China’s authoritarian government.

Huawei writes the whole thing off as one big misunderstanding and says that it complies with laws in global markets: “We respect the integrity of intellectual property rights—for our own business, as well as peer, partner and competitor companies,” the company said.

The US had done little to confront Huawei head-on up until the last couple of months. This allowed the Chinese giant to grow bigger than companies like Cisco and Motorola, while at the same time settling civil litigation along the way without admitting fault.

Robert Read, a former contract engineer from 2002 to 2003 in Huawei’s Sweden office said:

“They spent all their resources stealing technology. You’d steal a motherboard and bring it back and they’d reverse-engineer it.”

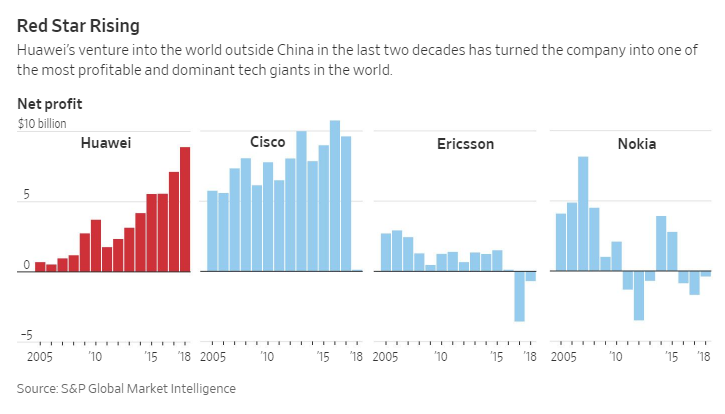

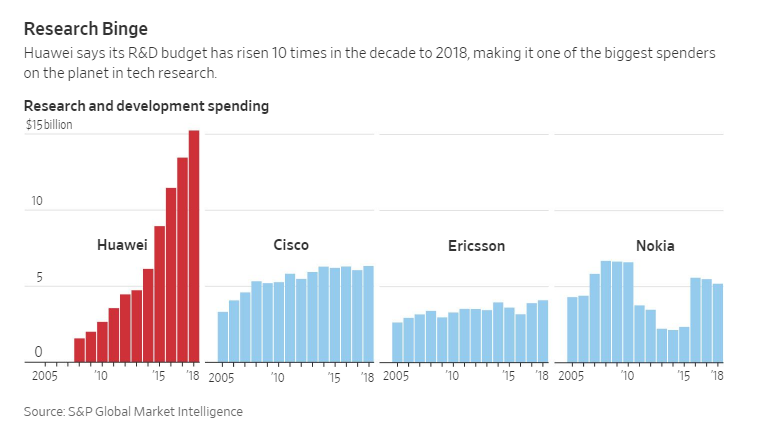

Huawei had a research budget of $15.2 billion last year, second only to Google, Amazon and Samsung.

And Huawei’s business tactics can be easily ignored by their customers, because of how advanced – and how cheap – their technology is. Its prices are often 20% to 30% less than competitors. Huawei was able to grow revenue 20% last year, to more than $100 billion as a result. Joseph Franell, chief executive of Eastern Oregon Telecom said: “We have found their equipment to be the most reliable. We haven’t had a single equipment failure from Huawei. That’s an astounding record.”

Back in the early 2000’s, when the company started, it kept somewhat of a low profile, especially when opening offices in Plano, Texas and Santa Clara, California. Jan Ekström, senior adviser to Huawei’s Swedish office from 2004 to 2017 said:

“They didn’t want to put out the sign on the building saying: Here is Huawei.”

Even then, staff were reportedly briefed to recruit talent from rivals. Former Stockholm employees recall foreign made equipment being shipped back to China to be dissected by engineers. Huawei had also built spy-proof secure rooms that were off-limits to American employees in its U.S. offices. This pointed to the company handling information like a state intelligence service, instead of a technology company. Huawei claims the rooms were installed to prevent spying against the company.

In 2003, Cisco accused Huawei of stealing its software and its manuals. “They have made verbatim copies of whole portions of Cisco’s user manuals,” Cisco said in its lawsuit. The plagiarism was so flagrant that Huawei even copied bugs in Cisco’s software and typos that appeared in Cisco’s manuals also appeared in Huawei’s.

Huawei human resources manager Chad Reynolds in a court filing: “Huawei couldn’t release its routers for shipment until it fixed a substantial number of the common Cisco bugs contained in the Huawei routers.”

As a result, Cisco General Counsel Mark Chandler flew to Shenzhen to speak to Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei, who called it a “coincidence”. Huawei then settled the suit against it after admitting it had copied some of Cisco’s router software.

Around the same time, as competitor Ericsson was making layoffs in Stockholm, Read said that Huawei executives would give him money to buy rounds at the local bar for the laid off workers in hopes of enticing them to work for Huawei.

William Plummer, former head of government relations at Huawei’s Washington, D.C., office said that the company also benefitted from a hiring spree after the dot com bubble burst: “A lot of this talent was thrown to the wind because everyone else was savaged. It was nothing magical. Just timing,” he said.

By the time 3G rolled around, Huawei had made large strides, with its global market share growing to 18% from 6% and with revenue rising about 15 fold, to $30 billion, by 2011.

As the company grew, major companies like Qualcomm, Microsoft and Intel became suppliers for it. And at the time, nobody wanted to make formal complaints about allegations of stealing in the tech world. David Hickton, former U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania said: “That problem had been going on for a long time. The companies didn’t want to make waves with China.”

But that didn’t stop Motorola from coming forward in 2010 and alleging Huawei of stealing their technology for a compact base station that connects devices in a wireless network called the SC300. Motorola accused one of its employees – a relative of Huawei founder Ren – of flying back to Beijing to secretly show Huawei trade secrets for the device.

An e-mail from the employee’s laptop showed him writing to Ren after the meeting, stating: “Attached please find those documents about SC300 specification you asked.”

One of the employee’s alleged co-conspirators was arrested in 2007 after being stopped at Chicago O’Hare with a one way ticket to Beijing and more than 1,000 documents that included Motorola trade secrets. She was convicted of stealing trade secrets in 2012.

Meanwhile, Motorola had dropped its lawsuit as Beijing launched an antitrust probe of Motorola’s sale of its network business to Nokia. Michael Wessel, a member of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission said: “China took retribution against a number of companies, using antitrust, anti-money laundering, state secrets, a number of things, that sent shock waves through the community.”

One week after Motorola said it would make peace with Huawei, the Chinese government approved the sale to Nokia.

And as Huawei emerges as a dominant player in 5G, allegations of theft continue. For instance, David Barker, the chief technology officer of Quintel Technology Ltd., an Anglo-American developer of network antennas was pitched an idea called “user specific tilt” by a company who claimed they got it from Huawei. The technology “could multiply the number of signals from an antenna and tilt them to provide greater accuracy in communicating with mobile phones.”

Baker knew of an identical type of technology – his own. He had coined the same concept and called it “per user tilt” 7 years prior, according to a lawsuit against Huawei. Baker’s company had shared the idea with Huawei in 2009 after the Chinese company had proposed a partnership. The lawsuit against Huawei was eventually settled.

Emil Björnson, an engineering professor at Sweden’s Linköping University, said the technology is in use today: “Today these are in the networks. They may not call it ’user-specific tilt,’ but that is it in its most elementary form.”

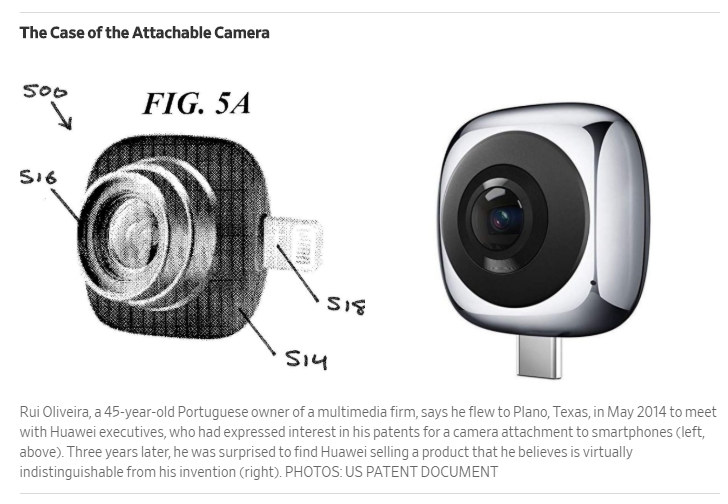

And Rui Oliveira, a 45-year-old Portuguese multimedia producer, met with Huawei in 2014 to pitch them the idea of a camera attachment to smartphones. After being told “we’ll talk later” by Huawei execs, he was asked by a friend three years later why the Chinese tech giant was “selling his camera”.

And indeed, it appeared they were. Huawei’s camera was identical to his – and being sold at the same $99.99 price point he had pitched. “I felt robbed,” Oliveira said.

When he threatened to sue Huawei, they turned around and sued him, instead. And the legal fight for those without corporate backing is a massive – if not impossible – challenge.

Paul Cheever, a school teacher who records kids music, said his life has been “overrun” by paperwork since he sued Huawei in California last year. He alleges the company stole his song “A Casual Encounter” and pre-loaded onto its smartphones for free. He found out when, on YouTube, people were leaving comments on his song attributing it to Huawei phones.

“It’s a weird feeling having this company take my song and give it away to 100 million people on the devices without my permission,” he said.

Both current and former employees told the WSJ that the company places “intense pressure” on delivering results. In 2016, founder Ren called the company’s expansion a “saturated attack” on competitors and likened it to a military campaign. During a speech in April, he said: “Our carrier network business group will be fighting a ferocious war in the next 10 years. We must be psychologically prepared.”

In the early 2010’s in the U.S., Huawei engineer Xiong Xinfu had been tasked with getting information on trying to duplicate a robot called “Tappy” that was being produced by T-Mobile.

He eventually stole part of the robot in 2013 and T-Mobile won a lawsuit against Huawei for $4.8 million as a result.

U.S. prosecutors went after Huawei for the same case in Federal court this year, stating: “A civil resolution doesn’t necessarily resolve whether and how serious a federal crime was committed, or whether justice was served.”

Congress declared Huawei a national security threat in 2012.