Meet The Mastermind Behind JPMorgan’s Gold And Silver Manipulation Crime Ring. There was a time when the merest mention of gold manipulation in “reputable” media was enough to have one branded a perpetual conspiracy theorist with a tinfoil farm out back. That was roughly coincident with a time when Libor, FX, mortgage, and bond market manipulation was also considered unthinkable, when High Frequency Traders were believed to “provide liquidity”, when the stock market was said to not be manipulated by the Fed, and when the ever-confused media, always eager to take “complicated” financial concepts at the face value set by a self-serving establishment, never dared to question anything.

All that changed in November 2018 when a former JPMorgan precious-metals trader admitted he engaged in a six-year spoofing scheme that defrauded investors in gold, silver, platinum, and palladium futures contracts. John Edmonds, then 36, pled guilty under seal in the District of Connecticut to commodities fraud, conspiracy to commit wire fraud, commodities price manipulation, and spoofing, a trading technique whereby traders flood the market with “fake” bids or asks to push the price of a given futures contract up or down toward a more advantageous price, and to confuse other traders or HFTs which respond to trader intentions by launching momentum in the other direction. As FBI Assistant Director in Charge Sweeney explained at the time, “with his guilty plea, Edmonds admitted he intended to introduce materially false and misleading information into the commodities markets.”

A little more than a year later, former Deutsche Bank precious metals trader David Liew sat in a federal courtroom telling a jury about how he learned to ‘spoof’ markets from his colleagues, and that he considered the behavior to be “OK” because it was “so commonplace.” Unfortunately for him, federal authorities didn’t see it that way, and have aggressively prosecuted the big dealer banks for market manipulation across a variety of markets. His testimony led to convictions for two of his former coworkers. A few days later, JP Morgan agreed to settle similar allegations with a record $1 billion fine, netting another major victory for the government in the nearly decade-long campaign to root out manipulation from the precious metal markets.

Today, Bloomberg is finally catching up to years of “conspiracy theory” reporting, such as this article published here in 2014 and titled “Gold Rigging By Bullion Banks Exposed: The Complete Chart“, with a sweeping expose about the precious metals manipulation and spoofing scandal, focusing on the precious metals trading desk at JPM and its top trader, Mike Nowak.

And although Bloomberg inexplicably did not mention it even once in its lengthy report, Nowak’s desk was under the direct purview of Blythe Masters, who from 2007 until 2014 was the head of Global Commodities at JPMorgan.

Which is ironic because going all the way back to 2012, the “tinfoil hat” crowd was abuzz with speculation that central banks, perhaps in league with the big broker dealers and occasionally aided by HFT momentum ignition, were conspiring to manipulate precious metals prices. When questioned about this in an interview with CNBC, Masters denied that JPMorgan was engaged in any manipulation, and instead insisted that JPM’s precious metals desk was reputable a “client-driven business.”

“Our business is a client-driven business where we execute on behalf of clients to help them with their…risk management objectives,” Blythe Masters said before going on to claim that the bank runs a “balanced book”, where its long and short positions are always evened out. But the punchline was when Master, who is perhaps best known for discovering the Credit Default Swap, said that manipulating markets to benefit the bank’s positions to the detriment of clients would be “wrong, and we don’t do it.”

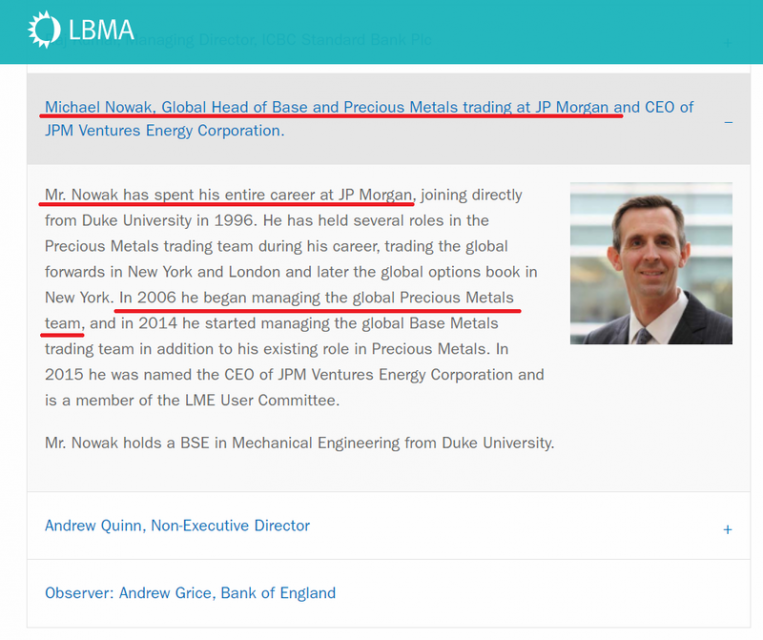

Masters quietly quit JPM two years later – perhaps sensing that the regulators are starting to sniff around the precious metals business and just after she was named by FERC for organizing the manipulation of power markets in California and the Midwest (JPM settled for $410 million). Unfortunately for her former subordinate, Mike Nowak, who until recently was the top JPM precious metals trader, he is now in the crosshairs of a unprecedented RICO case alleging his trading desk operated like an ongoing criminal conspiracy due to its abuse of “spoofing” a strategy that has been blamed as illegal market manipulation that may have caused the 2010 flash crash. But more on Blythe in a second.

In a lengthy feature detailing the federal investigation into Nowak’s desk, Bloomberg reveals how Nowak’s scheme was exposed to the world after regulators came knocking and former subordinates turned against him, and how the ‘spoofing’ practice’ first arrived at JPMorgan alongside several new faces from Bear Stearns, which JPM “bought” back in 2008 in a government-backstopped deal for pennies on the dollar.

Testimony from Edmonds and other turncoat traders might help earn guilty verdicts against Nowak and three co-defendants from JPM. If prosecutors win more guilty verdicts against Nowak and his team, it could set a new precedent for how the big banks use tools like RICO to go after the big banks.

In charging Nowak and others, prosecutors are testing an unusual application of a law formulated to battle mobsters, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. Prosecutors say Nowak’s trading desk was a criminal racketeering operation within the confines of America’s biggest bank. Traders on Nowak’s desk engaged in spoofing as a core business practice, doing it more than 50,000 times over nearly a decade, they said..

The Justice Department has famously used the RICO statute to bring down mafia bosses and drug gangs. It has used other statutes to extract penalties and guilty pleas from big banks accused of market manipulation. But it’s been decades since the government has attempted to apply the anti-racketeering law to members of a major bank’s trading desk, placing Nowak and others in crosshairs once trained on the likes of the Latin Kings and the Gambino crime family.

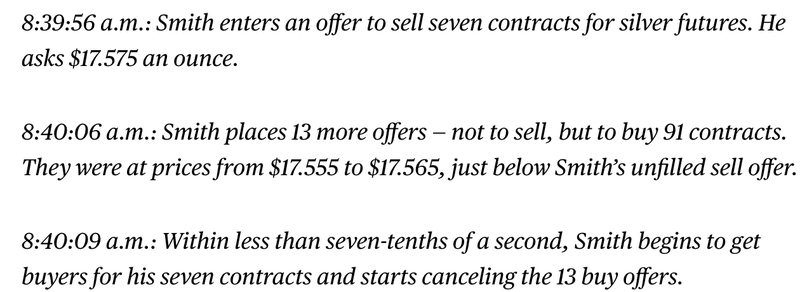

What does a typical spoofing look like?

As has traditionally been the case in various DoJ cases against Wall Street spoofers, the evidence includes Bloomberg extensive and damning trader chat transcripts obtained by the court. Bloomberg offers an example early in the report.

At that point, instead of consummating the purchase, Nowak received an instant message from a Bear Stearns manager across the street: “Smith just bid it up to … sell.”

Here’s another none-too-subtle exchange.

While much of the details behind the DOJ case had already been known to the market, for the first time the report explained how federal prosecutors based in Connecticut initially stumbled on to the JPM precious metals desk. As the DoJ was upping its focus on market manipulation with cases involving FX and other asset classes, prosecutors started looking for patterns in the raw trading data provided by the exchanges. When they looked for individual traders cancelling a bevy of orders on one side while executing on the other, they noted it as a possible example of spoofing. Quickly, trades made by Edmonds and other members of Nowak’s desk stood out.

One can imagine that when prosecutors decided to ‘shake the tree’ and confront Edmonds with the evidence he quickly folded. The team soon secured another cooperating witness from the Bear Stearns side, and they were off.

The arrest of Nowak – who was also on the board of the LBMA (which described itself as the “the world’s authority on precious metals”) until he was kicked off in Sept 2019 once the charges against him were revealed sent a shockwave through the industry as others wondered whether they could also come under scrutiny: because “if he could come under scrutiny, couldn’t anyone?”

Nowak’s trial is on pace for next year, according to filings in the case. One expert said the odds will be stacked against Nowak since the government should be able to use a JPMorgan settlement in its favor.

“The company — and all its information and all of its personnel — is now sitting at the prosecutors’ table,” one lawyer said.

Curiously, in a non-too trivial defense, Bloomberg explained that Nowak believed that spoofing was more or less required to help human traders fend off algorithm-driven HFT firms from siphoning up all the profits. He may have a point. Here is how Bloomberg describes the attempt by upstart HFTs market manipulators to steal market share from such established manipulators are JPM:

For generations, metals changed hands in open-outcry pits where hundreds of traders screamed prices and obscenities. Nowak, introverted and brainy, came along in time for electronic trading and the problems it posed. Firms and individuals with fast internet connections and proprietary algorithms were swarming in and out of positions to profit on small daily price moves.

For long-time readers, none of this is news – after all this is precisely the dynamic we explained first in 2009 and watched it grow and flourish for much of the 2010s. At the same time, some of the most notable traders across Wall Street were directly engaging with these HFTs in a furious battle of life and death, as humans constantly tried to outsmart the machines. One such approach was to spoof them (HFT powerhouse Citadel recently filed a lawsuit it was “defrauded” by humans who successfully spoofed its algos).

Traders at big operations like JPMorgan’s found that within a second of placing a bid, their price was often countered by high-frequency traders who would match and close a position before the traders had a chance to complete their deal. These algos not only snapped up trades but also created momentum in the market that pushed prices away from the traders’ targets.

This too was explained all the way back in 2018 in “”Momentum Ignition” – The Market’s Parasitic ‘Stop Hunt’ Phenomenon Explained.” Back then it was also called a conspiracy theory. Turns out it wasn’t.

One way to outsmart them, current and former brokers and traders say, was to put up and remove an offer on the opposite side of the market. That would cause the algorithms to recalculate market supply and demand, leaving an opening for the traders to get the deal done at the price they wanted.

Early on, some of Nowak’s traders were attempting to counter the algos by placing a single large order opposite the one they wanted filled, according to prosecutors. The Bear traders’ twist was to place multiple orders, at different prices, that in aggregate were substantially larger than the genuine order — a technique the government calls layering. The orders, made in rapid succession after the genuine order, would be canceled as soon as the genuine order was filled. Think of it like trying to sell a hamburger. You conjure a mob in front of your burger joint, creating the perception of demand. Once a real customer steps up and buys the burger, you make the mob vanish.

While this strategy is familiar to everyone who wishes to create a buzz – such as the fake lines to buy iPhones in front of Apple stores – the problem is that in capital markets at least, spoofing is illegal. Unfortunately, since HFTs were also legal – and they should never have been allowed in a post Reg-NMS world – it left traders relying on their own devices to outsmart the robots, and that’s why spoofing became more and more popular and prevalent.

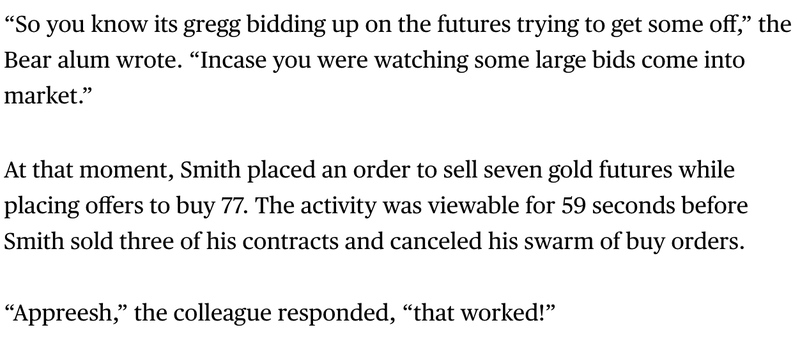

The layering worked in futures markets in part because participants see a second-by-second barrage of offers to buy and sell, but not who’s making them. And whereas one big order might stand out, a lot of small ones might not. That made it important to warn colleagues when layering was in progress. One of the former Bear traders did just that for a new JPMorgan colleague in early 2009, according to prosecutors.

“So you know its gregg bidding up on the futures trying to get some off,” the Bear alum wrote. “Incase you were watching some large bids come into market.”

At that moment, Smith placed an order to sell seven gold futures while placing offers to buy 77. The activity was viewable for 59 seconds before Smith sold three of his contracts and canceled his swarm of buy orders.

“Appreesh,” the colleague responded, “that worked!”

Altogether, Smith, a lead gold trader, executed some 38,000 layering sequences over the years, or about 20 a day, prosecutors said in filings. (Smith has pleaded not guilty). Nowak himself primarily traded options, but he would dip into the futures market to hedge those positions. He tried his hand at layering in September 2009, according to filings, and went on to use the technique some 3,600 times.

So what was the damage?

Well, according to the government, JPMorgan’s traders caused tens of millions of dollars in losses for those on the other side of the transactions – which included not just HFTs but regular, retail traders – and “harmed market integrity.” As a result, JPMorgan’s precious metals trading desk — which brings in as much as $250 million in annual profit — generated millions of dollars in unlawful gains.

What may explain the brazen manipulation not only at JPM but at every other abnk is that the CFTC – those toothless regulators once led by late Bart Chilton – looked into allegations of market manipulation of the silver market by JPMorgan not once, not twice, but three times… and found nothing (to much mockery).

Nowak, who held leadership roles on the LME and the London Bullion Market Association, was asked to explain the bank’s trading. In 2010, he sat for two days of interviews with CFTC investigators, explaining the bank’s trading strategies.

“To your knowledge, have traders at JPMorgan in the metals group put up bids and offers to the market which they didn’t intend to execute and then pulled them before they got hit or lifted?” one CFTC investigator asked.

“No,” Nowak responded.

The CFTC closed the third of those three inquiries in 2013 without taking action. JPMorgan has cited those CFTC investigations while defending against civil lawsuits, accusing plaintiffs of rehashing “implausible theories” of silver futures manipulation that were rejected by regulators.

It turns out those theories were not only plausible but true, and they were only validated thanks to an upstart, young prosecutor name Avi Perry, an assistant U.S. attorney in Connecticut with a Yale law degree. As Bloomberg puts it “Perry didn’t set out to target JPMorgan’s operation so much as JPMorgan’s trading found him.”

Perry started hunting for market manipulation around 2018, as the Justice Department was upping its game in the area. For years, prosecutors had built market manipulation cases by following up on tips and pulling trading data on suspects. Now they were doing deep dives into raw data to uncover targets, parsing records filed directly with the exchanges.

In the real-time scrum of futures markets, where offers are made and pulled all day long, it’s nearly impossible to discern potential manipulation. But the government had an edge. The data feed of the trades includes each trader’s exchange credentials, allowing investigators to sort for suspicious patterns and attribute it to individuals.

Perry also had a valuable guide to the market. His lead FBI investigator, Jonathan Luca, previously worked as a gold and silver futures trader at Morgan Stanley. Together, they created a screen for precious metals trading data. The idea, according to two people familiar with the analysis, was to turn up sequences in which a trader placed and canceled a profusion of orders on one side of the market while executing a trade on the other. The bigger the mismatch between genuine and pulled offers, and the more a given trader did it, they said, the more it would be considered a red flag for potential spoofing.

When they ran the screen, traders at JPMorgan stood out.

The rest is history, and two years later JPMorgan is facing a record $1 billion wrist-slap, which one assumes is a fraction of the profits the bank made by manipulating gold and silver for over a decade, and a few traders are set to spend a few months in “Club Fed”-style minimum security prisons.

It didn’t come without complications though. Readers may recall one of the other notable gold manipulator names mentioned here over the past decade, that of UBS former gold desk head in Zurich, Andre Flotron walked after Perry failed to present a convincing case and most of the charges against the former UBS gold trader were dismissed and he was acquitted. Defense lawyers and even some fraud prosecutors wondered if the government’s spoofing initiative was waning, according to Bloomberg.

But Perry did not give up and in 2018 his bosses recruited him for a job at the Justice Department’s fraud section in Washington, whose prosecutors have built some of the biggest U.S. corporate crime cases. With the trading analysis in hand, he went looking for individuals who might talk.

It’s unclear how Perry and the FBI approached Edmonds, who at times had placed orders with as many as 400 contracts on the opposite side of a genuine one, but they likely did so without raising alarms inside JPMorgan. Edmonds had left JPMorgan in 2017 after declining the bank’s offer to relocate to Singapore, and by the fall of 2018 was working at another bank.

Perry and his team talked to Edmonds at least twice in the weeks before he traveled to Connecticut to enter his secret guilty plea on Oct. 9, 2018.

Several months later, Perry secured the cooperation of one of the Bear traders who moved to JPMorgan. Pleading guilty, that trader said he personally manipulated trades while working from offices in New York, London and Singapore, and said spoofed trades were a fixture at the bank for nearly a decade.

However, in Nowak’s office there was little sign of dark clouds. Although banks often place individuals on leave when legal action may be pending, Nowak and Smith remained at their desks well after the charges against Edmonds were made public in November 2018.

Things then rapidly escalated, and to prosecutors, the evidence fit the template for a racketeering conspiracy, aka RICO, most famously used in cases against mafia families in the 1970s — a pattern of illegality over time, with individuals working together to further the goals of the allegedly criminal enterprise. Racketeering charges were leveled against Michael Milken in 1989 but dropped when he reached a settlement with authorities. The statute was successfully applied in the early 1990s against eight traders in the Chicago Mercantile Exchange soybean pits, according to Bloomberg.

Using the RICO template, by the summar of 2019, Perry had secured the government’s indictment of Nowak, Smith and a third trader. It was filed under seal in federal court in Chicago, where the trades took place. The charges were made public in September, and Nowak appeared in handcuffs in federal court in Newark, New Jersey — accused of conspiracy to participate in or conduct a criminal racketeering enterprise, attempted price manipulation, bank fraud, wire fraud, commodities fraud and spoofing. In addition to the half-dozen people who’ve been charged, the government documents referred to seven more individuals as unindicted co-conspirators. It’s not clear whether any of them have cooperated or what additional information they may have provided in the year since.

Nowak’s trial is scheduled for next year, and the government should be able to use the recent $1 billion JPMorgan settlement to its favor, Bloomberg said citing Michael Koenig, a former federal prosecutor who’s now a partner at Hinckley, Allen & Snyder who added that “the company — and all its information and all of its personnel — is now sitting at the prosecutors’ table.”

* * *

Yet now that all the “tinfoil” conspiracy theories involving the JPMorgan commodity trading desk have been confirmed, the bank is set to pay $1 billion to settle all ongoing legal cases (and is yet another reason why Jamie Dimon is richer than you), and a bunch of traders may go to prison for a few months, one name is strangely missing.

That of Blythe Masters, the person who was in charge of all JPMorgan commodity trading in the period 2007 – 2014 when most of these traders got their start in the spoofing business.

While we wait to find out how and why the DOJ missed this key JPMorgan staffer who supervised and made the spoofing possible for nearly a decade, and who was previously busted by FERC for similarly manipulating the energy market in California and Michigan (because merely rigging gold prices was not enough for the bank that also wanted to moonlight as Enron), we will remind readers of an interview Masters gave to CNBC in 2012 in which a primary topic, ironically, was whether or not Jamie Dimon’s firm manipulates the prices of precious metals, and particularly silver.

What followed was – as we know now – an avalanche of lies:

- “JPM’s commodities business is not about betting on commodity prices but about assisting clients”… “it’s about assisting clients in executing, managing, their risks and ensuring access to capital so they can make the kind of large long-term investments that are needed in the long run to expand the supply of commodities”…

- “There’s been a tremendous amount of speculation particularly in the blogosphere on this topic. I think the challenge is it represents a misunderstanding as the nature of our business. As i mentioned earlier, our business is a client-driven business where we execute on behalf of clients to achieve their financial and risk management objectives. The challenge is that commentators don’t see that. So to give you a specific example, we store significant amount of commodities, for example, silver, on behalf of customers we operate vaults in New York City, Singapore and in London. And often when customers have that metal stored in our facilities, they hedge it on a forward basis through JPMorgan who in turn hedges itself in the commodity markets. If you see only the hedges and our activity in the futures market, but you aren’t aware of the underlying client position that we’re hedging, that would suggest inaccurately that we’re running a large directional position. In fact that’s not the case at all.

- “We have offsetting positions. We have no stake in whether prices rise or decline. Rather we’re running a flat or relatively flat matched book.

And the punchline from the 2012 interview:

“What is commonly out there is that JPMorgan is manipulating the metals market. It’s not part of our business model. it would be wrong and we don’t do it.”

Eight years later, JPMorgan is paying $1 billion because it was manupalting the metals market and was lying about it. Which begs the question: does this mean that manipulation is also part of JPM’s business model? We can’t wait for someone to ask Jamie Dimon this question at the upcoming JPMorgan earnings call

Source: Bloomberg