A number of analysts is actually talking such hot theme – How U.S. shale can survive the oil crash?

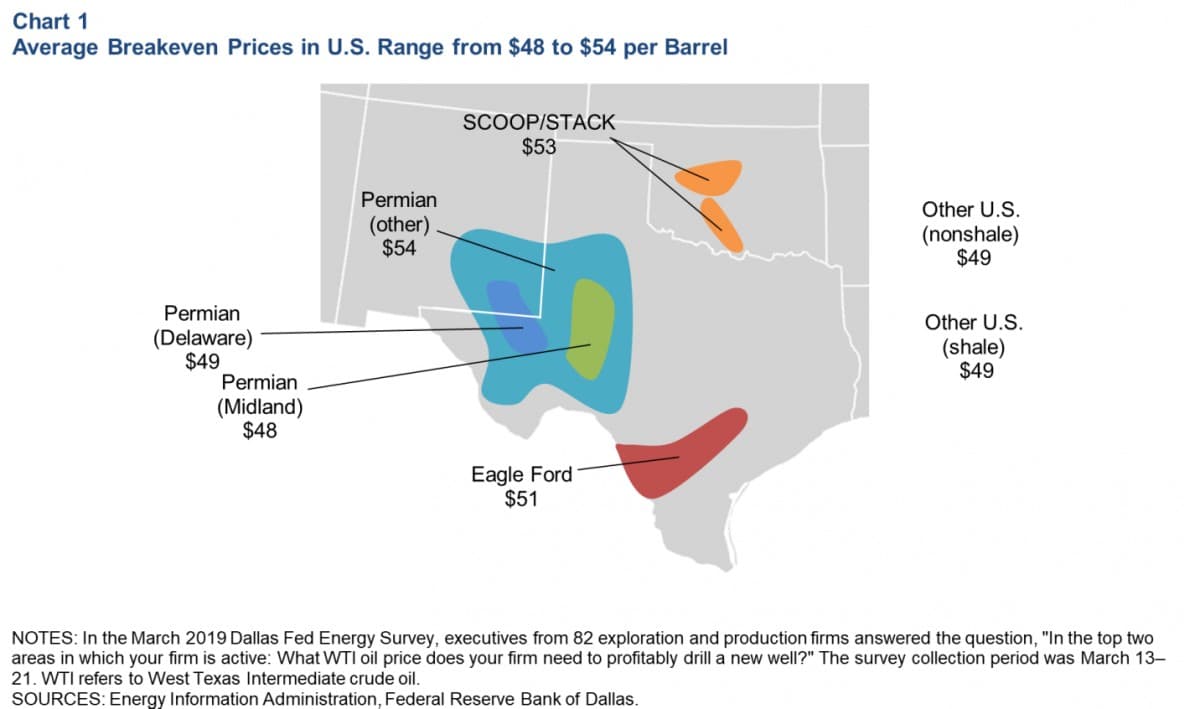

The question regarding whether we have reached peak oil demand is a pressing concern for U.S. upstream activity. U.S. tight oil’s current cost structure, which generally requires ~$50/barrel WTI to make it economically viable, suggests that oil demand needs to return to pre-COVID levels for U.S. shale to recover (Fig. 1). This article considers the industry’s ability to lower its cost structure further in order for it to maintain competitiveness.

So precisely how can the well-touted U.S. industry’s ingenuity and willpower be brought to bear? The breadth of companies creates a robust laboratory of ideas. Further, as this essay details, there are several options the industry can pursue to lower its costs and/or raise productivity. It is also the case that lower prices yield savings for oil companies in terms of taxes and royalties worth several $/barrel [bbl]). However, it is also true that the realizing the next $15/bbl of cost reduction appears much more difficult than the last $15/bbl. Such a significant reduction of cost for most of U.S. unconventional production may require some as yet unforeseen technology, systems, or operations innovation, as well as greater-than-expected access to capital. Put these pieces together, and it is tempting, therefore, to predict that only a portion of U.S. productive capacity can achieve these thresholds over the medium term.

We identified four categories of opportunities to lower U.S. unconventional per barrel costs:

1) royalty and tax relief from lower hydrocarbon prices;

2) reduction of overhead costs, including from consolidation;

3) increased use of digital technologies/artificial intelligence in the field, and;

4) continued evolution in optimizing both the “drainage” of the reservoir and operating cost management.

5) liquidating all assets, hedging against another crash.

1. Oil companies get tax and royalty relief with lower prices. The companies pay royalties to the owners of the mineral rights based on the value of produced hydrocarbons. As a result, royalty obligations are directly related to the price of oil and natural gas. Using the traditional royalty rate of 12.5%, if the realized sale price is $30/bbl vs. 2018’s average West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price of $64.90/bbl, the implied reduction in royalty is $4.35/bbl. Severance taxes paid to state and local governments are also primarily based on the value of production, with significant producing states (including Texas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and North Dakota) having effective tax rates of 4-8%. Using the aforementioned oil price differential, the implied savings is $1.50-$2.50/bbl.

2. Overheads can be reduced further, including through consolidation. General and administrative (G&A) expenses at U.S. independent upstream oil companies often run $2-3/bbl of oil produced. In the current landscape, as with other downturns, oil companies are focusing on lowering their G&A and operating costs, with an eye on finding sustainable savings (e.g., taking out layers of management or closing regional offices), along with savings that are more cyclical or variable in nature. Consolidation offers opportunities for sustainable costs savings, including combining many so-called “back office” and corporate functions. Further, larger, and better-capitalized companies presumably will have more access to, or a lower cost of, external capital as a result.

3. Automation of wellsite activity is still in relatively early days, but a clear focus for many companies. The savings and productivity opportunity associated with digitization of the oilpatch is the most difficult (in this short list) to estimate, but appears to be considerable. Most tangible in the near term would be the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) capabilities related to drilling. AI can, as an example, integrate reservoir information obtained as drilling is underway to adjust direction and drilling parameters automatically relative to the original well plan. Such techniques can help drill wells (a) more quickly, (b) with fewer individuals on location (in part as more tasks can be overseen remotely) and (c) that are “cleaner” (defined as having lower “tortuosity”), which facilitates production. Still nascent, but emerging, is the automation of hydraulic fracturing. That is, using AI to set parameters dynamically to maintain greater consistency, and thus more evenly distribute proppant across the well. This should raise well productivity (and offers a side benefit for the hydraulic fracturing company in that it can ease strain on the equipment by pumping jobs at lower pressure).

4. Continued adoption of best practices still has running room, albeit likely with diminishing returns. Many shale development efficiencies have been realized over the past several years, including: larger scale operations, a better understanding of the reservoir that can help determine optimal well spacing and placement, upgraded and more efficiently maintained equipment (in part a function of using Big Data to drive predictive maintenance), use of produced natural gas to power field equipment, and more accurate placement of wells. The previous categories about consolidation and digitization can also drive adoption of best practices. For example, consolidation, particularly of contiguous acreage, can help scale up operations, which among other benefits can facilitate drilling longer lateral wells, and building larger hydrocarbon-gathering or water-handling systems.

5. Liquidating all assets, hedging against another crash. By far the smart way. Next crash mean Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Russia will flood market with $15 oil. End of “fossil” era.

This set of five opportunity categories has clear implications for the U.S tight oil competitiveness challenge. Even if much of the sector can substantially lower per barrel costs, it will still mean fewer companies and fewer employees. This does offer some benefits, including that staff can be removed from some of the most hazardous working conditions at the well site. Yet, the conclusion is that the U.S. upstream industry must likely shrink in order to hold its ground, which implies it becomes a relatively smaller part of the U.S. and specific states’ economies, albeit one with greater financial and competitive resilience.