Back in the late fall of 2014, when Saudi Arabia broke up OPEC for the first time and unleashed a torrent of crude oil on the world despite the protests of its fellow cartel members, oil prices crashed as a result of what then seemed to be a “calculated” move by Riyadh which hoped to put US shale out of business amid a flawed gamble betting that shale breakeven prices were around $60-80. They, however, turned out to be much lower, which coupled with Saudi misreading of the willingness of junk bond investors to keep funding US shale producers, meant that despite a 3 years stretch of low oil prices, US shale emerged stronger than ever before, with the US eventually eclipsing both Saudi Arabia and Russia as the world’s biggest crude oil producer.

Fast forward to March 2020, when Saudi Arabia doubled down in its attempt to crush shale, only to avoid angering long-time ally Donald Trump, the Crown Prince pretended that the latest flood of oil was an oil price war aimed at Moscow not Midland. And this time, unlike 2014, with the benefit of the global economic shutdown resulting from the coronavirus pandemic, the Saudis may have finally lucked out in the ongoing crusade against US oil, because as Bloomberg writes with “negative oil prices, ships dawdling at sea with unwanted cargoes, and traders getting creative about where to stash oil”, the next chapter in the oil crisis is now inevitable: “great swathes of the petroleum industry are about to start shutting down.”

As the recent OPEC summit so vividly demonstrated, the marginal price of oil is no longer determined by supply or cuts thereof (such as the recently announced agreement by OPEC+ for a 9.7mmb/d output cut), but rather by demand, or the lack thereof, which according to some estimate is as much as 36mmb/d lower, or roughly a third of the global oil market every day, as billions of people are stuck at home instead of driving, while major corporations mothball production in a world where major economies have ground to a halt.

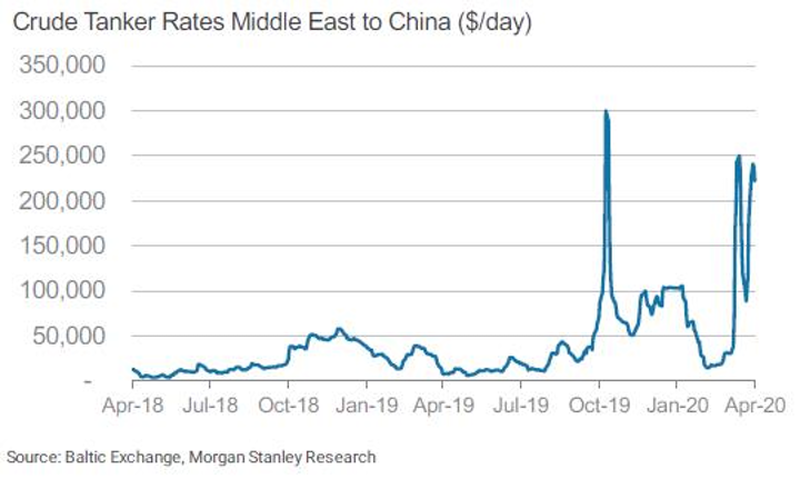

Now shipping prices are climbing to stratospheric levels as the industry runs out of tankers, a sign of just how distorted the market has become.

Ironically, in its latest attempt to kill off shale, Saudi Arabia may have gone a step too far, as “the specter of production shut-downs – and the impact they will have on jobs, companies, their banks, and local economies – was one of the reasons that spurred world leaders to join forces to cut production in an orderly way. But as the scale of the crisis dwarfed their efforts, failing to stop prices diving below zero last week, shut-downs are now a reality. It’s the worst-case scenario for producers and refiners.”

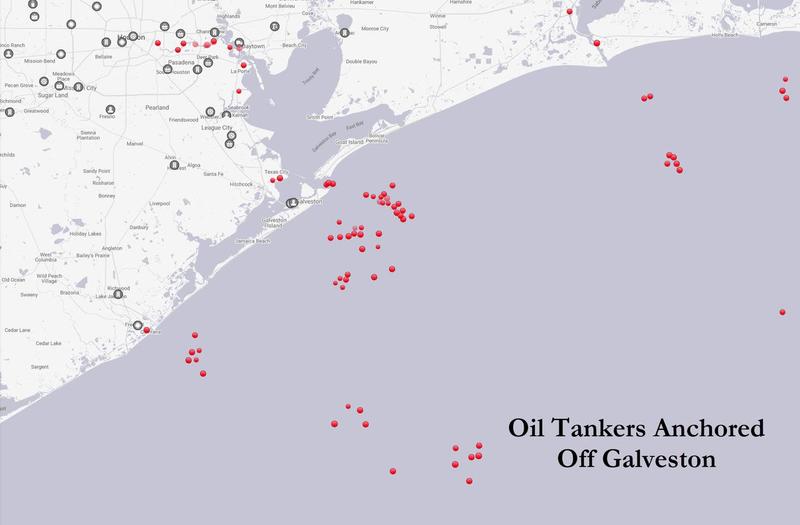

n short, the entire oil production industry is shutting down, not because it wants to – of course – but because it has no choice. According to Goldman, in as little as three weeks there will be literally no place left on earth to store oil, and unless oil producers want to pay “buyers” to hold the oil as happened on that historic date of April 20, they have no choice but to shut in output.

“We are moving into the end-game,” said Torbjorn Tornqvist, head of commodity trading giant Gunvor Group. “Early-to-mid May could be the peak. We are weeks, not months, away from it.”

Which brings us back to why in 2020 Riyadh has succeeded where it failed in 2014: as Bloomberg writes “in theory, the first oil output cuts should have come from the OPEC+ alliance, which earlier this month agreed to reduce production from May 1. Yet after the catastrophic price plunge on Monday, when West Texas Intermediate fell to -$40 a barrel, it’s the U.S. shale patch that is leading”

The best indicator of how the shale industry is reacting is the sudden collapse in the number of oil rigs in operation, which last week fell to a four-year low: “Before the coronavirus crisis hit, oil companies ran about 650 rigs in the US. By Friday, more than 40% of them had stopped working, with only 378 left.”

And so the US industry is finally shutting down as ConocoPhillips and shale producer Continental Resources have all announced plans to shut in output. Regulators in Oklahoma voted to allow oil drillers to shut wells without losing leases; New Mexico made a similar decision. Even North Dakota, which for years was synonymous with the U.S. shale revolution, is witnessing a rapid retrenchment, as Bloomberg notes that “oil producers have already closed more than 6,000 wells, curtailing about 405,000 barrels a day in production, or about 30% of the state’s total.”

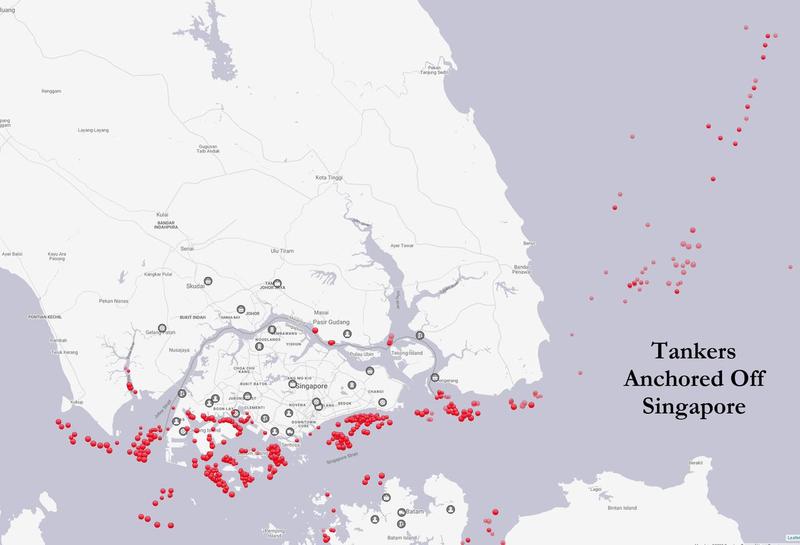

And what is going on in that tanker parking lot off of Singapore is absolutely insane.

British Petroleum Announces $4.4 Billion Quarterly Loss

Earlier this month, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its allies agreed to reduce oil production by 9.7 million barrels per day in May and June, followed by 7.7 million per day for the second half of the year, and then by 5.8 million per day until April 2022.

The oil and gas giant BP on Tuesday has reported a $4.4 billion net loss in the first quarter of this year after global demand dropped dramatically amid the COVID-19 pandemic, as a UK-based industry body has warned of 30,000 job cuts in the oil and gas industry over the next 18 months.

When accounting for the underlying numbers, BP’s replacement cost profit was $791 million in the first quarter of the year, down from $2.6 billion in the fourth quarter of 2019.

“Our industry has been hit by supply and demand shocks on a scale never seen before. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with pre-existing supply and demand factors have resulted in an exceptionally challenged commodity environment,” BP’s new chief executive Bernard Looney said.

The losses were concentrated in the significant decline in the worth of inventory holdings, which totalled $3.7 billion.

On the same day, industry body Oil and Gas UK said that based on current estimates, 30,000 jobs will be lost from the UK’s oil and gas industry over the next 12-18 months, should government efforts to prop up the sector fail.

Oil demand across the world has slumped amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has grounded passenger planes and halted economic activity across the globe. On April 20, the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil for May delivery fell to a negative value for the first time in history due to limitations in storage space.

OPEC+ countries have sought to stabilize the global oil market amid the unprecedented decline in demand and subsequent price drop. On April 12, member states signed an agreement committing to cut production by 9.7 million barrels per day from May-June. Thereafter, output will be reduced by 7.7 barrels from July until the end of 2020, and by 5.8 million barrels per day from January 2021 to April 2022.