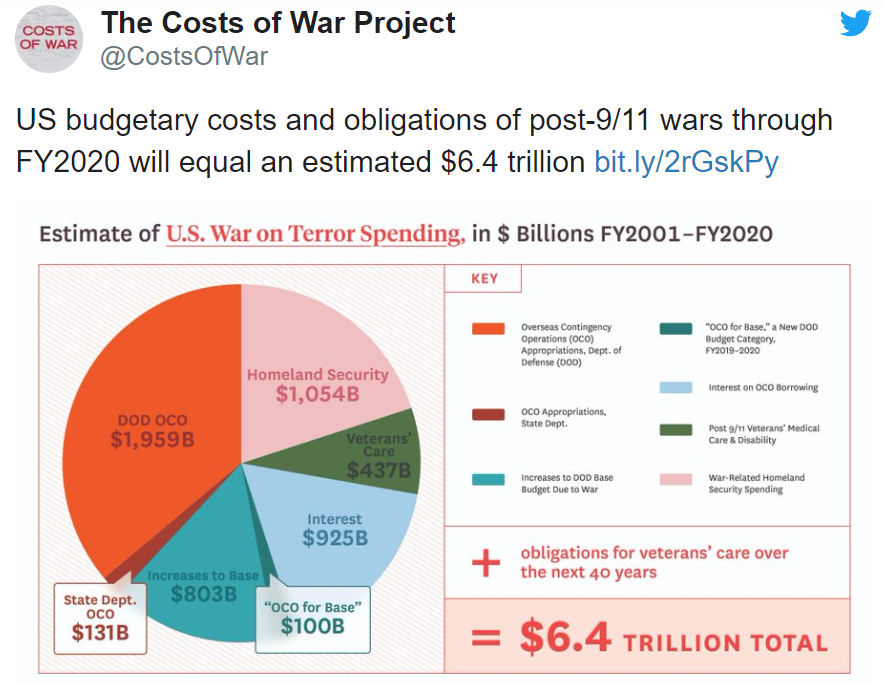

The so-called War on Terror launched by the United States government in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks has cost at least 801,000 lives and $6.4 trillion according to a pair of reports published Wednesday by the Costs of War Project at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

“The numbers continue to accelerate, not only because many wars continue to be waged, but also because wars don’t end when soldiers come home,” said Costs of War co-director and Brown professor Catherine Lutz, who co-authored the project’s report on deaths.

“These reports provide a reminder that even if fewer soldiers are dying and the U.S. is spending a little less on the immediate costs of war today, the financial impact is still as bad as, or worse than, it was 10 years ago,” Lutz added. “We will still be paying the bill for these wars on terror into the 22nd century.”

The new Human Cost of Post-9/11 Wars report (pdf) tallies “direct deaths” in major war zones, grouping people by civilians; humanitarian and NGO workers; journalists and media workers; U.S. military members, Department of Defense civilians, and contractors; and members of national military and police forces as well as other allied troops and opposition fighters.

The report sorts direct deaths by six categories: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria/ISIS, Yemen, and “Other.” The civilian death toll across all regions is up to 335,745 — or nearly 42% of the total figure. Notably, the report “does not include indirect deaths, namely those caused by loss of access to food, water, and/or infrastructure, war-related disease, etc.”

Indirect deaths “are generally estimated to be four times higher,” Costs of War board member and American University professor David Vine wrote in an op-ed for The Hill Wednesday. “This means that total deaths during the post-2001 U.S. wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Pakistan, and Yemen is likely to reach 3.1 million or more —around 200 times the number of U.S. dead.”

“Don’t we have a responsibility to wrestle with our individual and collective responsibility for the destruction our government has inflicted?” Vine asked in his op-ed. “Our tax dollars and implied consent have made these wars possible. While the United States is obviously not the only actor responsible for the damage done in the post-2001 wars, U.S. leaders bear the bulk of responsibility for launching catastrophic wars that were never inevitable, that were wars of choice.”

Referencing the project’s second new report, United States Budgetary Costs and Obligations of Post-9/11 Wars Through FY2020: $6.4 Trillion (pdf), Vine wrote, “Consider how we could have otherwise spent that incomprehensible sum — to feed the hungry, improve schools, confront global warming, improve our transportation infrastructure, and provide healthcare.”

“At a time when everyone from Donald Trump to Democratic Party candidates for president is calling for an end to these endless wars, we must push our government to use diplomacy — rather than rash withdrawals, as in northern Syria — to end these wars responsibly,” he concluded. “As the new Costs of War report and 3.1 million deaths should remind us, part of our responsibility must be to repair some of the immeasurable damage done and to ensure that wars like these never happen again.”

The project’s $6.4 trillion figure accounts for overseas contingency operations appropriations, interest for borrowing for OCO spending, war-related spending in the Pentagon’s base budget, medical and disability care for post-9/11 veterans (including estimated future obligations through FY2059), and Department of Homeland Security spending for prevention of and response to terrorism.

Costs of War co-director and Boston University professor Neta Crawford co-authored the project’s death toll report and authored the budget report. For the latter, she wrote that “the major trends in the budgetary costs of the post-9/11 wars include: less transparency in reporting costs among most major agencies; greater institutionalization of the costs of war in the DOD base budget, State Department, and DHS; and the growing budgetary burden of veterans’ medical care and disability care.”

Both reports were released as part of the project’s new “20 Years of War” series. Crawford, Lutz, and fellow Costs of War co-director Stephanie Savell were in Washington, D.C. Wednesday to present the reports’ findings at a briefing hosted by the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services.

“We have already seen that when we go to Washington and circulate our briefings, they get used in the policymaking process,” Lutz said in a news story published by Brown Wednesday. “People cite our data in speeches on the Senate floor, in proposals for legislation. The numbers have made their way into calls to put an end to the joint resolution to authorize the use of military force. They have real impact.”

Lutz pointed out that “if you count all parts of the federal budget that are military-related— including the nuclear weapons budget, the budget for fuel for military vehicles and aircraft, funds for veteran care — it makes up two-thirds of the federal budget, and it’s inching toward three-quarters.”

“I don’t think most people realize that, but it’s important to know,” she added. “Policymakers are concerned that the Pentagon’s increased spending is crowding out other national purposes that aren’t war.”