Raymond Dalio – an American billionaire investor, hedge fund manager, and philanthropist. Dalio is the founder, Co-Chairman and Co-Chief Investment Officer of investment firm Bridgewater Associates, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, posted a grim warning not only to the investor community.

Ray Dalio: The Next Logical Steps In A Dangerous Journey To War, The 1935-45 Analog

Regarding that classic dangerous journey, you have heard me describe it many times but, at the risk of boring you, I will repeat it. I believe that we are on a classic journey that we haven’t seen in our lifetimes but has happened many times before, most recently in the late 1930s.

It is being driven by the same big forces that drove the dynamics in the late 1930s. In particular, now, like in the late 1930s and unlike any period since, these three big forces are converging.

They are:

- The largest wealth and political gaps since the late 1930s exist, which is leading to the emergence of and conflicts between populists of the left and populists of the right. If history and logic are to be our guides, it seems reasonable to worry that the gaps between the rich and the poor and the populists of the left and the populists of the right will become more war-like and that the consequences of their fighting could undermine the efficient operation of the economy as well as the efficient running of government. History has shown, logic suggests, and what seems to be happening is that the greater conflict leads to a) the reduced respect for both law and the art of compromise by our political leaders, and b) the increased testing of relative powers and the increased use of “emergency powers” to gain and use more power than these acts were intended for. It is likely that the upcoming US elections will be the greatest ideological clash that we have seen in our lifetimes, approaching the extreme fascist-communist clashes of the 1930s. It is likely that after the election there will be many more conflicts, tax law changes, and wealth redistributions that will have big implications for markets and economies.

- There is limited ability of the world’s reserve currency central banks to stimulate the economy in the event of an economic downturn. When I imagine what the next economic downturn will be like with the social and political polarity that now exists, I expect it will be socially and politically ugly and that some form of “Monetary Policy 3” (see this May 2019 article) will have to happen or the economic depression won’t be rectified. To implement MP3-type monetary policy will require very large fiscal spending and large budget deficits that will have to be funded by a) substantially increased taxes on companies and the rich, and b) the printing of money by central banks and the buying of the debts that are coming from the deficits. Typically, this has led to capital flight as investors seek to escape these things, which has quite often led to capital controls that are intended to keep capital in the country and the currency so that it can more easily be taxed and/or devalued. So, naturally, I can’t help but wonder whether this extraordinary (i.e., nothing like this has happened in my lifetime) deviation from convention to restrict capital flows to China could be followed by these other steps when/if the circumstances that I’m describing unfold.

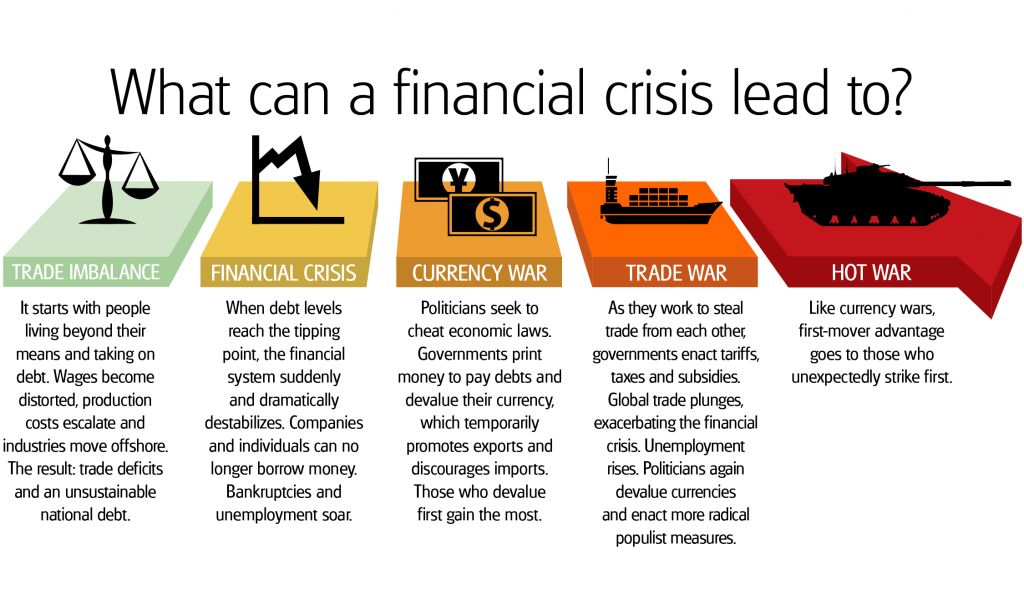

- There is a rising power (China) challenging the existing world power (the US), which will probably lead to more conflicts between them about many different issues. History has shown that this situation has led to the increased risk of wars that typically come in four forms: trade wars, capital wars, technology wars, and geopolitical wars. As far as the trade wars go, you can see them for yourself (so I won’t delve into them) and probably have yourself drawn comparisons with the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs in 1930 and with various tariffs in several countries during the 1930s. Regarding the capital and currency wars, the ability of the US president to unilaterally cut off capital flows to China and also freeze payments on the debts owed to China and also use sanctions to inhibit non-American financial transactions with China must be considered as possibilities. That’s why the proposed step of limiting American portfolio investments in China makes me both think about the implications of this step and wonder if it is an inching toward bigger moves.

For perspective about what can be done and how it would be done, one can look at the US freezing of Japanese assets and embargoing of oil to Japan in the late 1930s to early ‘40s; they show how the use of special emergency powers gives the president the ability to do these things. Emergency powers today are most accessible to the president under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA). It empowers the president to unilaterally impose capital and FX controls, freeze assets and/or payments on assets (coupons), and force asset divestures to “deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat” from outside the US to “the national security…economy of the United States.” Just the realization that these moves can be used has important implications for capital flows. For example, how would you feel if you were an adversarial foreign investor holding US bonds given this situation, given where US bond interest rates are and the impending deficits and monetizations of them? Of course, China dumping US bonds would have its own terrible consequences too. In any case, from not having to worry about such things in the past, now all market participants need to worry about them.

Regarding the technology war, we have seen the tip of the spear with Huawei, and we (Bridgewater) have given you an extensive look at the moves we can imagine could be done by both sides, so I won’t embellish more on them. As far as the geopolitical war is concerned, it’s a war of influence that is being fought in the classic Chinese way of quietly gaining strength and showing that strength to one’s opponent so that they realize that it is better to retreat than to fight. That is certainly happening in Asia and, to a lesser extent, in other parts of the world.

Countries are increasingly having to choose whether they are aligned with the US or China. When presented with this choice, they typically answer it based on both economic and military calculations. Almost without exception, they say that the economics favors being aligned with China because China is more important to them economically (because China is bigger in trade and bigger in capital inflows) and that the military support favors the US if the US is willing to use it to support them, which is highly doubtful.

At the same time, China’s own military capabilities (including cyber) are rising relative to the US’s, especially in Asia. As a result, China is for the most part quietly winning the geopolitical war, particular in Asia. As for what is likely to happen next, the big thing is the 2020 elections because that will determine who the players are; until then, actions and agreements are more for theater to play to the crowd than the real deal. After the elections, the real picture will emerge. Longer term, barring any big shocks, time is on China’s side as it is improving at a faster rate than the US, and the big question is whether the world will:

a) peacefully evolve toward two different spheres of influence, with China the dominant force in the East and the US the dominant force in West, or

b) have more painful wars of their various types.

Under each of these three broad categories of influences, I have imagined a detailed sequence of events for how these dynamics will progress, based on how sequences of events have classically played out in the past and how it is logical they will play out nowadays. I do this so I can compare how events transpire relative to expectations. If they’re largely the same, I assume the sequence will continue as imagined, and if they’re different, I abandon my theory and recalibrate.

To me, last week’s developments seemed like the most recent logical steps in this classic dangerous journey that is analogous with that which occurred in the 1935-45 period.

Four Appendices

What follows are four appendices.

- Appendix 1 provides a more detailed account of what actually happened, what can happen, and how it can happen pertaining to threats to curtail capital flows to China.

- Appendix 2 recounts the path to war in the late 1930s via excerpts from my book “Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises” (available in pdf form here for free).

- Appendix 3 recounts various times monetary policies didn’t work because there was “pushing on a string” and provides the various Monetary Policy 3-type fiscal/monetary coordinations that occurred in the past.

- Appendix 4 provides the legal basis for capital controls and capturing the assets of foreign entities.

Appendix 1: A More Precise Account of What Happened, Why, and What Is Likely to Happen

To be precise, two narrow measures are being examined by the administration.

- The first narrow step under consideration by the White House is whether to support/push for Senator Marco Rubio’s Equitable Act legislation. The Equitable Act outlines a process for the delisting of a Chinese firm from US stock exchanges if it doesn’t fully comply with US accounting and oversight regulations, e.g., audit requirements. Senator Rubio notes that China’s government has long been reluctant to allow overseas regulators to inspect local accounting firms—including member firms of the Big Four international accounting networks—citing national security concerns, and that a 2013 agreement allowing US regulators to request audit working papers in China has not been effectively implemented. Resultantly, in December 2018, the SEC and the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) flagged the difficulties US regulators faced in inspecting the audit work and practices of auditing firms in China that examine US-listed Chinese companies.

- The second narrow measure under discussion is a potential ban (or restriction) precluding the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board from including the MSCI All Country World ex-US Index in the ~$50 billion Federal Employees Retirement Fund (FERF, the government’s main retirement savings fund) in 2020. Senator Rubio and other members of Congress who support such a ban argue that retirement assets of federal government employees, including members of the US Armed Forces, will be exposed to “severe and undisclosed material risks” associated with many of the Chinese companies listed on this MSCI index.

Why Are These Things Happening?

The motivations and objectives driving these discussions appear varied: from wanting to enforce US accounting and oversight regulations in order to engender reciprocity (Senator Rubio’s Equitable Act bill), to curtailing access to US capital by certain Chinese firms implicated by national security concerns (restricting FERF’s planned MSCI offering), and ultimately to decoupling US and China capital markets so as to undermine China’s rise. There are officials (Peter Navarro) who seek to limit China’s access to US capital, as they think such access strengthens the Communist Party in China—an economic rival and rising geostrategic competitor with different values antithetical from the US/West. Recently, Steve Bannon characterized the goal this way: “The Frankenstein monster that we have to destroy is created by the West. It’s created by our capital.” There are other officials trying to circumscribe these measures and keep them separated from trade negotiations so as not to inflame tensions, sink markets, and weaken the real economy. Some officials, on the other hand, reportedly see these measures as giving the US increased leverage in the trade negotiations with China at a critical juncture. All these US officials appear to share concerns about US capital enabling Chinese firms when the lines of demarcation between state-owned and private firms are further eroding. They are concerned with the unusual influence the Chinese government has over private firms, including placing restrictions on the release of financial information of Chinese firms. And, importantly, they want to counter industrial policies such as President Xi’s new “military-civil fusion” directed at enhancing cooperation between China’s technology firms and the military and Made in China 2025.

These discussions, in turn, are taking place days before Vice Premier Liu He’s expected visit to Washington for high stakes talks on October 10-11. These talks importantly will play out in the shadow of scheduled US tariff increases, a potential Xi-Trump meeting, and the pending expiration of Huawei licenses. In particular, i) on October 15 tariffs are scheduled to increase to 30% from 25% on $200 billion in imports from China; ii) there is a scheduled meeting on November 16-17 between Xi and Trump at the APEC Summit; iii) on November 19 Huawei’s general temporary license is due to expire, and iv) on December 15 tariffs are scheduled to be imposed on $160 billion of the most politically sensitive Chinese imports (consumer products of high value to US consumers with no readily available substitutes (~87% sourced from China)).

Appendix 2: The 1930s Path to War (Excerpted from Part 2 of “Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises,” Which Was about the 1930 – 1941 Period)

While the purpose of this chapter has been to examine the debt and economic circumstances in the United States during the 1930s, the linkages between economic conditions and political conditions, both within the United States and between the United States and other countries—most importantly Germany and Japan—cannot be ignored because economics and geopolitics were very intertwined at the time. Most importantly, Germany and Japan had internal conflicts between the haves (the Right) and the have-nots (the Left), which led to more populist, autocratic, nationalistic, and militaristic leaders who were given special autocratic powers by their democracies to bring order to their badly managed economies. They also faced external economic and military conflicts arising as these countries became rival economic and military powers to existing world powers.

To help to convey the picture in the 1930s, I will quickly run though the geopolitical highlights of what happened from 1930 until the official start of the war in Europe in 1939 and the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. While 1939 and 1941 are known as the official start of the wars in Europe and the Pacific, the wars really started about 10 years before that, as economic conflicts that were at first limited progressively grew into World War II. As Germany and Japan became more expansionist economic and military powers, they increasingly competed with the UK, US, and France for both resources and influence over territories. That eventually led to the war, which culminated in it being clear which country (the United States) had the power to dictate the new world order. This has led to a period of peace under that world order and will continue until the same process happens again.

More precisely:

- In 1930, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff began a trade war.

- In 1931, Japan’s resources were inadequate, and its rural poverty became severe, so it invaded Manchuria, China to obtain natural resources. The US wanted to keep China free from Japanese control and was competing for natural resources—especially oil, rubber, and tin—from Southeast Asia, while at the same time Japan and the US had significant trade with each other.

- In 1931, the depression in Japan was so severe that it drove Japan off the gold standard, leading to both the floating of the yen (which depreciated greatly) and big fiscal and monetary expansions that led to Japan being the first country to experience a recovery and strong growth (which lasted until 1937).

- In 1932, there was a lot of internal conflict in Japan, which led to a failed coup and a massive upsurge in right-wing nationalism and militarism. During the period from 1931 to 1937, the military took over control of the government and increased its top-down command of the economy.

- In 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany as a populist promising to exercise control over the bad economy, to bring order to the political chaos of the democracy of the time, and to fight the communists. Within just two months of being named chancellor, he was able to take total authoritarian control; using the excuse of national security, he got the Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act, which gave him virtually unlimited powers (in part by locking up political opponents and also by convincing some moderates that it was necessary). He promptly refused to make reparations payments, stepped out of the League of Nations, and took control of the media. To create a strong economy and attempt to bring prosperity to the people, he created a top-down command economy. For instance, Hitler was involved with setting up Volkswagen to build a more affordable car and directed the building of the national German Autobahn (highway system). He believed that Germany’s potential was limited by its geographic boundaries, that it didn’t have adequate raw materials to feed the industrial military complex, and that German people should be ethnically united.

- At the same time, Japan became increasingly strong with its top-down command economy, building a military-industrial complex, with the military intended to protect its bases in East Asia and northern China and to expand its controls over other territories.

- Germany also got stronger by building its military-industrial complex and looking to expand and claim adjacent lands.

- In 1934, there was severe famine in parts of Japan, causing even more political turbulence and reinforcing the right-wing, militaristic, and nationalistic movement. Because the free market wasn’t working for the people, that led to the strengthening of the command economy.

- In 1936, Germany took back the Rhineland militarily, and in 1938, it annexed Austria.

- In 1936, Japan signed a pact with Germany.

- In 1936–37, the Fed tightened, which caused the fragile economy to weaken, and other major economies weakened with it.

- In 1937, Japan’s occupation of China spread, and the second Sino-Japanese War began. The Japanese took over Shanghai and Nanking, killing an estimated 200,000 Chinese civilians and disarmed combatants in the capture of Nanking alone. The United States provided China’s Chiang Kai-shek government with fighter planes and pilots to fight the Japanese, thus putting a toe in the war.

- In 1939, Germany invaded Poland, and World War II in Europe officially began.

- In 1940, Germany captured Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France.

- During this time, most companies in Germany and Japan remained publicly owned, but their production was controlled by their respective governments in support of the war.

- In 1940, Henry Stimson became the US Secretary of War. He increasingly used aggressive economic sanctions against Japan, culminating in the Export Control Act of July 2, 1940. In October, he ramped up the embargo, restricting “all iron and steel to destinations other than Britain and nations of the Western Hemisphere.”

- Beginning in September 1940, to obtain more resources and take advantage of the European preoccupation with the war on their continent, Japan invaded several colonies in Southeast Asia, starting with French Indochina. In 1941, Japan extended its reach by seizing oil reserves in the Dutch East Indies to add the “Southern Resource Zone” to its “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” The “Southern Resource Zone” was a collection of mostly European colonies in Southeast Asia, whose conquest would afford Japan access to key natural resources (most importantly oil, rubber, and rice). The latter, the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” was a bloc of Asian countries controlled by Japan, not (as they previously were) the Western powers.

- Japan then occupied a naval base near the Philippine capital, Manila. This threatened an attack on the Philippines, which was at the time an American protectorate.

- In 1941, to aid the Allies without fully entering the war, the United States began its Lend-Lease policy. Under this policy, the United States sent oil, food, and weaponry to the Allied Nations for free. This aid totaled over $650 billion in today’s dollars. The Lend-Lease policy, although not an outright declaration of war, ended the United States’s neutrality.

- In the summer of 1941, US President Roosevelt ordered the freezing of all Japanese assets in the United States and embargoed all oil and gas exports to Japan. Japan calculated that it would be out of oil in two years.

- In December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and British and Dutch colonies in Asia. While it didn’t have a plan to win the war, it wanted to destroy the Pacific Fleet that threatened Japan. Japan supposedly also believed that the US would be weakened both by fighting a war in two fronts (Europe and Asia) and by its political system; Japan thought that totalitarianism and the command military industrial complex approaches of their country and Germany were superior to the individualistic/capitalist approach of the United States.

These events led to the “war economy” conditions, explained at the end of Part 1.

Appendix 3: Past Needs for and Ways of Executing Monetary Policy 3

Monetary Policy 3 puts money more directly into the hands of spenders instead of investors/savers and incentivizes them to spend it. Because wealthy people have fewer incentives to spend the incremental money and credit they get compared to less wealthy people, when the wealth gap is large and the economy is weak, directing spending opportunities at less wealthy people is more productive. Logic and history show us that there is a continuum of actions to stimulate spending that have varying degrees of control to them. At one end are coordinated fiscal and monetary actions, in which fiscal policy makers provide stimulus directly through government spending or indirectly by providing incentives for nongovernment entities to spend. At the other end, the central bank can provide “helicopter money” by sending cash directly to citizens without coordination with fiscal policy makers. Typically, though not always, there is a coordination of monetary policy and fiscal policy in a way that creates incentives for people to spend on goods and services. Central banks can also exert influence through macroprudential policies that help to shape things in ways that are similar to how fiscal policies might. For simplicity, I have organized that continuum and provided references to specific prior cases of each below.

- Fiscal/Monetary Coordination can take three basic forms:

- Increase in debt-financed fiscal spending, paired with QE that buys most of the new issuance (e.g., Japan in the 1930s, US during WWII, US and UK in the 2000s).

- Increase in debt-financed fiscal spending, where the Treasury isn’t on the hook for the debt, because:

a) The spending is paired with QE where the central bank retires the debt or commits to rolling the debt forever,

b) The central bank promises to print money to cover debt payments (e.g., Germany in the 1930s), or

c) Where the central bank directly lends to entities other than the government that will use it for stimulus projects (e.g., lending to development banks in China in 2008).

- Directly giving newly printed money to the government to spend, not bothering to go through issuing debt. Past cases have included printing fiat currency (e.g., Imperial China, the American Revolution, the US Civil War, Germany in the 1930s, UK during WWI) or debasing hard currency (Ancient Rome, Imperial China, 16th-century England).

- Printing money and doing direct cash transfers to households (i.e., helicopter money). When we refer to “helicopter money,” we mean directing money into the hands of spenders of money to get them to spend (e.g., the US veterans’ bonus during the Great Depression, Imperial China).

- How that money is directed could take different forms—the basic variants are a) to either direct the same amounts to everyone, or to aim for some degree of helping one or more groups over others (e.g., to the poorer more than to the rich), and b) to provide this money either as one-offs or over time (perhaps as a universal basic income). These variants could be paired with an incentive to spend it—like the money disappearing if not spent within a year.

- The money could be directed to specific investment accounts (like retirement, education, or accounts earmarked for small business investments) to target it toward socially desirable spending/investment.

- One potential way to craft the policy is to distribute returns/holdings from QE to households instead of to the government.

- Big debt write-down accompanied by big money creation (the “year of Jubilee”). (e.g., Ancient Rome, the Great Depression, Iceland).

While I won’t offer opinions on each of these, I will say that the most effective approaches involve fiscal/monetary coordination, because that ensures that both the providing and the spending of money will occur. If central banks just give people money (helicopter money), that’s typically less adequate than giving them that money with incentives to spend it. However, sometimes it is difficult for those who set monetary policy to coordinate with those who set fiscal policy, in which case other approaches are used.

Also, keep in mind that sometimes the policies don’t fall exactly into these categories, as they have elements of more than one of them. For example, if the government gives a tax break, that’s probably not helicopter money, but it depends on how it’s financed. The government can also spend money directly without a loan financed by the central bank—that is helicopter money through fiscal channels.

While central banks influence the costs and availabilities of credit for the economy as whole, they also have powers to influence the costs and availabilities of credit for targeted parts of the financial system through their regulatory authorities. These policies, which are called macroprudential policies, are especially important when it’s desirable to differentiate entities—e.g., when it is desirable to restrict credit to an overly indebted area while simultaneously stimulating the rest of the economy, or when it’s desirable to provide credit to some targeted entities but not provide it broadly. Macroprudential policies take numerous forms that are valuable in different ways in all seven stages of the big debt cycle. Because explaining them here would require too much of a digression, they are explained in some depth in the appendix of my book “Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises.” If you want to dig deeper, please review that appendix.

Appendix 4: The Legal Authorities of the President to Curtail Capital Flows

The president has broad, powerful, and mostly unilateral authority to regulate commerce (trade and finance) with foreign countries, under the executive’s emergency powers—codified in statute and reaffirmed by courts (courts have shown great deference to the president’s judgment in matters of foreign and national security). Key among them and one that President Trump has tapped and will likely tap for any meaningful curtailment of capital flows (e.g., foreign exchange controls) is the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977. §1701 of IEEPA empowers the president to declare a national emergency to “deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source…outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.” IEEPA gives the president discretion to “investigate,” “block,” “regulate,” “compel,” or “prohibit,” the “importation,” “transfer,” or “acquisition” of “property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.” §1702(a)(1)(B) of IEEPA empowers the president to act with respect to any person “subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.”

In the 42 years since its enactment, presidents have declared 54 national emergencies under IEEPA, 29 of which are ongoing. Presidents have tapped IEEPA to restrict a wide range of international transactions while expanding both the rationale for emergencies and targets of the restrictions, e.g., at first, targets were foreign governments, and later IEEPA was used to target individuals and non-state actors (terror groups). History (judicial precedent and congressional inaction) suggests that Trump could wield IEEPA with great force/impact, e.g., delisting Chinese companies on US stock exchanges, blocking all US-based transactions or freezing the US assets of any foreign firm or person, imposing currency controls or restricting FX purchases for certain or all foreign nationals, forcing divestment of US assets, blocking SWIFT payments system for foreign firms, and prohibiting US firms from outsourcing to China. President Trump cited IEEPA as the legal authority enabling his “order” that American companies “immediately start looking for an alternative to China.” Barring a successful court challenge, the only check on Trump’s IEEPA authority is Congress, which has yet to attempt to invalidate a national emergency. The political bar for congressional action is high—under IEEPA, Congress can invalidate a state of emergency via a joint resolution. The Supreme Court, however, has held that a joint resolution will not suffice. Congress must pass legislation to that effect, e.g., amend IEEPA to circumscribe the president’s emergency powers. Trump could then veto the legislation. And overriding a veto requires a two-thirds supermajority in both chambers.

Historical Precedent

There is much precedent for the president’s use of emergency powers before IEEPA. Before IEEPA’s enactment in 1977, the president’s emergency powers—enabling broad regulation of commerce (trade and financial)—were anchored in the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) of 1917. It was enacted after the US entered World War I. Section 5 of TWEA delegates to the president broad wartime powers to regulate all forms of international commerce and financial flows and to freeze or seize any foreign assets during a time of war. While the 1917 Act required a declaration of war, it was subsequently amended in 1933 to allow the president to declare a national emergency during peacetime. The declaration empowers the president with broad powers over both domestic and international transactions (the amendment came about due to the Great Depression, and President Roosevelt invoked Section 5(b) of the amended TWEA to declare a national emergency and order a bank holiday). Specifically, the 1933 amendment gave the president the authority to: “investigate, regulate, or prohibit…by means of licenses or otherwise any transactions in foreign exchange, transfers of credit between or payments by banking institutions…and export, hoarding, melting, or earmarking of gold or silver coin or bullion or currency by any person within the United States or any place subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” For example, with the objective of denying Germany access to Danish and Norwegian assets in the US, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8389, based on the authority vested in him by the TWEA Act as amended in 1933, to freeze all financial transactions involving (and assets of) Danes and Norwegians. In June 1941, President Roosevelt extended the freezing of assets to all of continental Europe under Executive Order 8785, backstopped by the TWEA.

Note: Ray missed the McCollum memo – An exact document how to provoke Japan to enter the war and attack Pearl Harbor: