The price of gold is $1,314 per ounce right now. But imagine if there was one place in the world – say Japan – where you could buy an ounce of gold for a fraction of that, $400.

By exporting and selling it at the world price, you’d have earned an easy $914 per ounce. This might sound too good to be true, but it’s precisely what happened in Japan in 1859. This post is about one of the greatest gold trades ever.

To understand how the greatest gold trade ever played out, we first need to delve into the years that preceded it.

Two centuries of isolation

By the early 1850s, Japan had been isolated from the rest of the world for over two hundred years. At the beginning of the 1600s, the ruling Tokugawa clan had adopted a policy of barring foreigners from entering the nation. The only point of Western contact was the Dutch trading post Dejima, an artificial island in the port of Nagasaki. But Western powers like the U.S. were anxious to trade with Japan too, so in 1853 U.S. commodore Matthew C. Perry was dispatched to negotiate a trade agreement.

Using the threat of force, Perry brought the Tokugawa shoguns to the bargaining table. In 1854, Perry managed to secure an opening of the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to U.S. vessels. This was a coaling agreement: it only allowed for the resupply and refueling of steam ships. A general commercial treaty would have to wait.

One of the complications that Perry ran into was determining how American ships were to make payments for coaling. For centuries, international trade had been dominated by the Spanish silver dollar (otherwise known as the Mexican dollar, pillar, eight real, or piece of eight), which was minted in Mexico as well as at several South American mints.

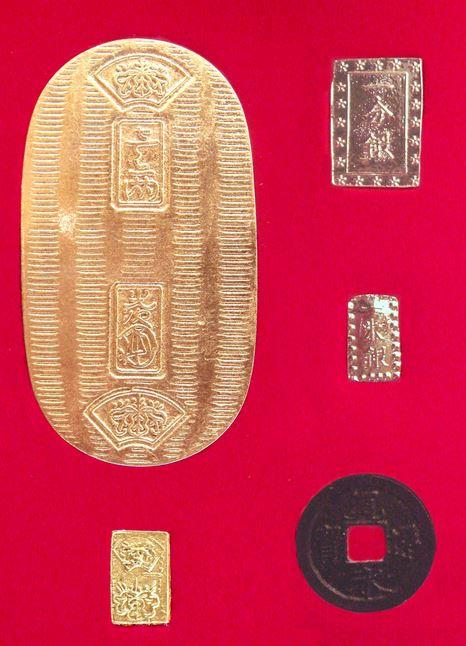

But Japan, having been closed off, did not typically deal in Spanish/Mexican dollars. It had its own unique set of coins and measurements. Prices were set in ryo, bu, and shu, with 1 ryo = 4 bu = 16 shu. The ryo was represented by a gold coin referred to as a koban. An ichibu silver coin was worth one bu, with four ichibus equal to 1 ryo, or one gold koban.

What was needed was an exchange rate between the dollar and the Japanese coins. To pay for the fueling of his ships at the newly-opened port of Hakodate, Perry ended up accepting the rate offered by his Japanese hosts: one Mexican dollar to one ichibu. Since four ichibus were equal to a gold koban, this meant that a Mexican dollar was worth 1/4 koban.

Gold Koban (upper left), silver Ichibu (upper right)

Spanish “Pillar” Dollar

This arrangement didn’t satisfy the Americans. A Mexican dollar weighed about three times an ichibu. Each dollar contained 25 gram of silver whereas an ichibu contained just a third of that, 8.5 grams of silver. Exchanging one Mexican dollar for one ichibu thus meant that the Americans were giving up two-thirds of the dollar’s silver content for free, or at least so it appeared to them.

With Perry having secured a small foothold on the island, Townsend Harris – the first US consul general to be appointed to preside in Shimoda – was tasked with prying Japan completely open to trade. In addition to negotiating a commercial treaty with the Tokugawa shogunate, Harris would also tackle the exchange rate controversy. Harris figured that if the exchange rate was set on a weight-for-weight basis, then one Mexican dollar would be the equivalent of three ichibu. In that way the silver bullion content of the two opposing coins would be equated, which to him only seemed fair.

Upon his arrival in September 1856, Harris immediately began to send letters to officials protesting the already-established one ichibu-to-one dollar exchange rate (Hanashiro, 1999). But he was unable to make much headway. For their part, the Japanese had excellent reasons for preferring the one ichibu-to-one dollar rate. When pressed by Perry and Harris, Japanese officials rightly pointed out that the ichibu was not like the Mexican dollar, which was valued according to its silver content. Rather, the ichibu was a token coin.

Token coins vs bullion coins

For readers of this post, token coins will be second nature. This is because all modern coin are tokens. A one-euro coin, for instance, weighs 7.5 grams, 75% of this copper, 15% nickel, and 10% zinc. The market value of this metal is around €0.05, far less than the coin’s face value of €1. This €0.95 gap between its commodity value and its face value is what qualifies the one-euro coin as a token.

Imagine that an alien beamed down to earth in 2019 and offered a Parisian the following deal. It will buy each of the Parisian’s 7.5 gram one-euro coins with a blank copper-nickel-zinc disc that weighs 7.5 grams. Would the Parisian take this offer? Of course not. She’d be giving up coins that trade for €1 a piece for discs that are worth a fraction of that amount.

In the same way that our Parisian would not want to accept the alien’s discs, the Japanese were understandably loath to trade away ichibus on a weight-for-weight basis. Like a euro coin, the ichibu’s value was supported not by its metal content but the authorities’ promise to accept it at a rate that far exceeded it bullion value. Selling ichibus to American on a weight-for-weight basis dramatically undervalued them, just like selling euro coins to an alien for metal discs would undervalue the euro.

It is possible that Harris and his American colleagues simply didn’t grasp the concept of token coinage. At the time, silver coins in the U.S. passed at their bullion value. Or perhaps they willfully ignored the ichibu’s status as a token. Whatever the case, Harris pressed his case until the Tokugawa government bowed to his demands. In the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the Japanese accepted a weight-for-weight exchange rate between the two types of coins, or three ichibus-to-one dollar.

This new relationship between the dollar and the ichibu destroyed the token status of the ichibu. Not only that, it created a terrific arbitrage opportunity between the Mexican dollar and the gold koban, thus laying the path for the 1859 gold mania.

The silver-gold arbitrage

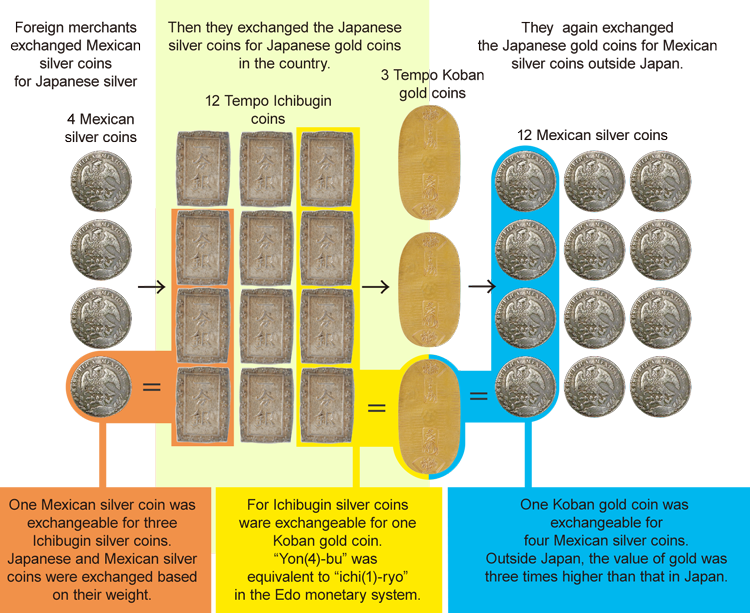

At the pre-Harris exchange rate of one ichibu-to-one dollar, there was no arbitrage opportunity between Mexican dollars and Japanese koban. An American trader could convert four dollars into four ichibus, which in turn could be traded at the Tokugawa shogunate’s official rate for one gold koban. A koban contained around 6.3 gram of yellow metal (Bytheway & Chaiklin, 2016).

After melting the koban and exporting it, the trader could sell this 6.3 grams of gold for silver at the world silver-to-gold ratio of 15.5:1, netting himself 98 grams of silver. With one Mexican dollar containing 24.5 gram of silver, 98 grams was the equivalent of four Mexican dollars. Thus, having originally spent four Mexican dollars in Japan, the American trader ended up with four dollars. There was no profit in carrying this trade out. Below at left, I’ve illustrated how things balanced out.

Harris’s 1859 weight-for-weight rule dramatically tipped the calculus of this trade in favour of the American side. Where before an American could convert four dollar into just four ichibus, now they were entitled to twelve ichibus. These twelve ichibu could in turn purchase three kobans, which together contained 19 gram of golds (6.8 grams each). On the international market, 19 grams of gold was worth 294 grams of silver, or 12 Mexican dollar (294 grams divided by 24.5 grams/per coin).

Thus, at the new rate, an American trader could magically turn four Mexican dollar into twelve Mexican dollars. By constantly recirculating silver and gold between the world market and Japan, it was theoretically possible to make infinite profits. (To understand the profitability of this trade, see calculation above at right). Below, the Bank of Japan Museum has provided a nice portrayal of this trade.

Delay tactics

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce took effect on July 4, 1859. But the great gold trade did not take off yet. Anticipating that foreigners would flock to exchange a dollar for an equal weight of Japanese silver coins, leading to a flood of gold out of the nation, the Japanese suddenly introduced a new coin, the nishu-gin. They had carefully calibrated the nishu’s specifications such that two nishus weighed as much as one Mexican dollar. So when it came to trade dollars for Japanese coins on a weight-for-weight basis, as stipulated in the Harris Treaty, Japanese officials could provide two nishu per dollar instead of three ichibus.

The nishu was given a face value of two shu. This meant that whereas it took just four ichibus to get a gold koban, it would take eight nishus to get a koban (1 koban = 1 ryo, and 16 shus = 1 ryo). Introducing the nishu effectively reestablished the pre-Harris exchange rate. An American trader’s four Mexican dollars could now be converted into eight nishus, and eight nishus into a koban. But the amount of gold in a koban was only worth four Mexican dollars in the world market, which was the original quantity of dollars spent to buy nishus. Having removed the gain to be made by selling dollars and purchasing kobans, Japanese officials had short-circuited the great gold trade.

The Americans were indignant, so the wary Japanese pulled the nishu off the market just a few weeks after introducing it. Now they relied on other tactics to cut off the great gold trade. Officials decreed that locals were not to sell gold kobans to foreigners. But this was evaded since kobans were easy to hide. They also limited the amounts of ichibus they made available. Huge lineups at official Japanese exchange offices developed as Westerners submitted claims to convert dollar into ichibus. But using money mules and straw names, traders could avoid their quotas:

“In October 1859, Thomas Eskrigge applied for three hundred and fifteen million dollars on behalf of Messers Bank, Rake, Nelly, Smell-bad, and No-nose… Another petition simply said, “Please change for me today $250,000,000 and much oblige.” (Frost, 1970)

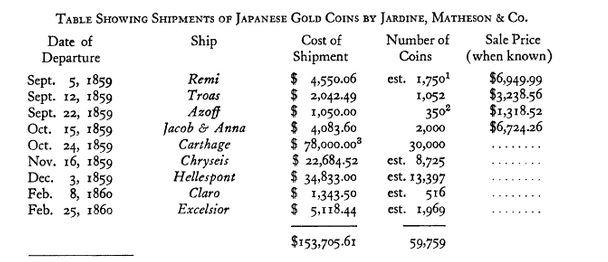

By the fall of 1859, the gold mania was in full flight. Ships left China for Japan with cases full of Mexican dollars and returned laden with kobans. Below is a list of the vessels dispatched by Jardine, Matheson & Company – a large British trading firm – including the quantity of koban exported (McMaster, 1960).

Estimates for the total number of koban sent out of Japan are wide-ranging. According to Bytheway & Chaiklin (2016), Japanese scholars have set a lower bound for koban exports of 100,000 (0.63 tonnes of gold) and an upper one of 20 million koban (126 tonnes). Let’s assume that 25 tonnes of gold was exported. Twenty-five tonnes of gold may not be much gold these days, but back in the 1860s this was quite a bit. Total above ground gold supply had only reached 7,000 tonnes of gold by the 1860s, and the world was only producing around 190 tonnes per year (Turk, 2012). Thus the amount of kobans that left Japan constituted a significant share of that year’s production.

The speculation comes to an end

Japanese officials brought the mania to an end after a few months. Foreigners were still allowed to convert their dollars on a weight-for-weight basis, and four ichibus could still be swapped for one koban. But the koban coin itself was now updated. The new koban that debuted in early 1860 contained just a third the gold that the old koban had contained. The image below illustrate the size of the debasement. This monetary reform had the effect of reducing the amount of gold that a dollar could purchase, thus cutting into the profit of a round-trip between China and Japan. The great gold trade was over.

The 1859 Japanese gold trade was great for all the westerners who profited from it. But it wasn’t so great for the Japanese. The Tokugawa government had earned much of its revenue through the issuance of token coins like ichibu. With token coins being replaced by less profitable bullion coins, that revenues source was gone. Faced with violent opposition, the last Tokugawa prince would resign in 1867.

The gold trade also pressured Japan’s feudal class structure. In an effort to accommodate themselves to foreigners’ conception of coinage, the Japanese government imposed a huge fall in the purchasing power of both the ichibu and koban. Anyone who earned an income denominated in these coins was suddenly much poorer. The Samurai warrior caste, many of whom lived off fixed stipends, was particularly hard hit. Samurai revolts would become a recurrent theme over the next few decades.

Many decades later, Japan remains an important gold market. The Tokyo Commodity Exchange, or TOCOM, is one of the largest gold trading venues in Asia. Following the liberalisation of the Japanese gold market in the 1970s, Japan became one of the world’s largest importers of gold during the 1980s and 1990s, fueled in part by an investment boom. But don’t go to Tokyo expecting to buy gold for $400 an ounce.

Source: Bank of Japan, BullionStar